I’m finally understanding Donald Trump’s appeal to a significant segment of the American public. I’ve been reading Albion’s Seed: Four British Folkways in America by David Hackett Fischer, the thesis of which argues that while most present-day Americans have no British ancestry, the four British regional cultures that were carried to North America by its early settlers have persisted into our own time. While in some ways Fischer’s model is a bit too pat, in the main it describes and contrasts the four settlement patterns of early America with analytical power.

I’m rereading the book as part of my research for my own memoir, the story of two diametrically opposed clans united in my parents’ marriage: Pennsylvania Quakers from the north Midlands of England and border residents from northern England, lowland Scotland, and northern Ireland, who Americans often refer to as Scots-Irish hillbillies. The other two regional cultures are represented by the Puritans from eastern England who settled New England and the small number of gentry and large number of indentured servants from the south of England who settled Virginia.

Fischer’s chapters on the Appalachian backcountry have been the most useful for me in not just understanding my own maternal lineage, but the appeal of a man like Donald Trump to a large swath of Americans, most of whom have no British ancestry and do not live in Appalachia. These folks are nonetheless the heirs of a particular worldview which traveled across the country with the many generations who settled further west.

It is no accident that Trump, one suspects at the advice of Steve Bannon, placed Andrew Jackson’s portrait in a place of honor in the Oval Office. Fischer uses Jackson as the prototype of a charismatic leader imbued with and sensitive to the values of this backcountry culture of honor, one as Fischer puts it that was “marked by extreme inequalities of condition” with a “public life … dominated by a distinctive ideal of natural liberty.”

Backcountry culture denigrated book learning, prized instinct, admired virility, despised authority, believed in retributive justice, demanded personal loyalty, brooked no dissent and “was apt to regard the terms opponent and enemy as synonymous.” Property crimes were treated as severe infringements on what was valued most: the right to acquire wealth. Crimes against the person such as assault, rape or even murder were often viewed as justified, or if not, a cause for extralegal retribution by the injured party or their family members. Violence was not just tolerated but celebrated.

Reputation is everything in this culture; a man protects his reputation by allowing no outside force to limit his freedom to do as he pleases. The circle within which one moves is proscribed by family and friends; outsiders are considered with suspicion. Strangers, especially of another race or culture, are treated as mortal threats. Authority structures beyond the clan are viewed as embodying the twin menaces of personal emasculation and cultural destruction.

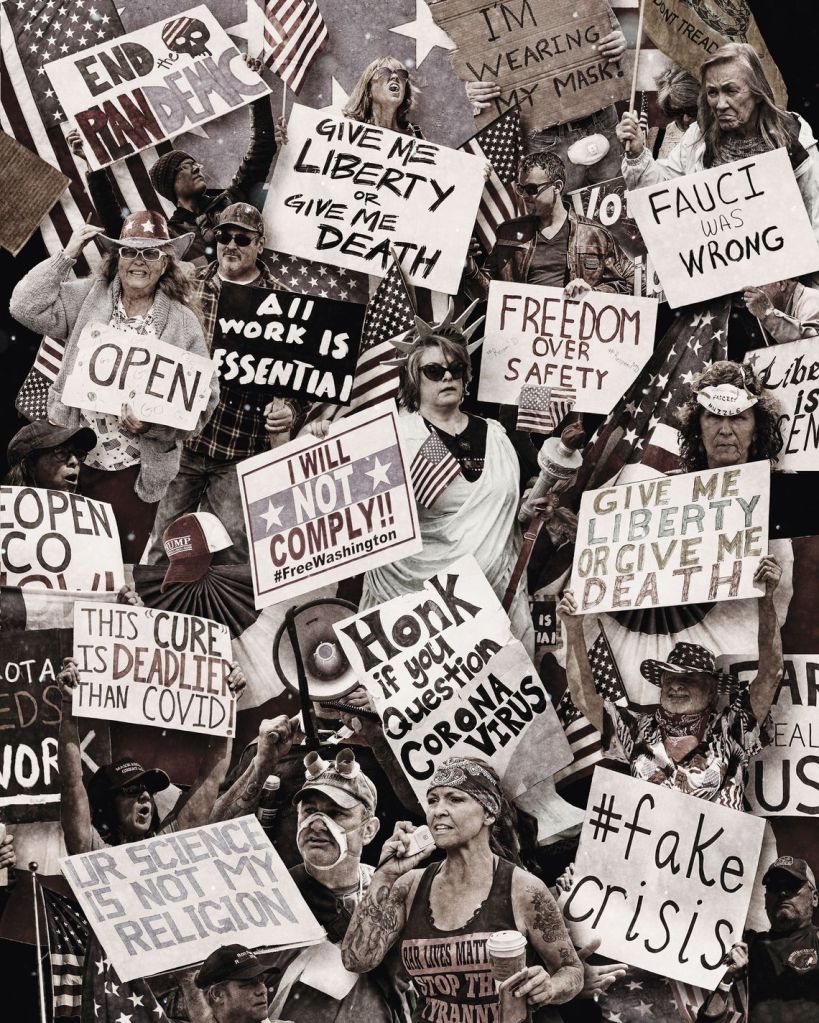

Which brings me to those protesting wearing masks, social distancing, and otherwise taking personal responsibility for stemming community spread of the coronavirus, the vast majority of whom are Trump supporters.

This morning’s Washington Post has an article written by a 63-year-old North Carolina store clerk with lifelong asthma. Her story is heartbreaking. Forced to be at work in a store catering to travelers on the Inland Waterway, she has had to resort to bolting the shop door shut, installing a doorbell and carrying mace. Customers have ignored the store’s requirement to wear a mask, refused her offer of curbside delivery, shouted obscenities at her while trumpeting their individual rights. Inveighing against the W.H.O. is common, as are threats of violence and accusations of complicity in “the Deep State.”

All of these behaviors would be seen as righteous in the eighteenth century backcountry or in Andrew Jackson’s early nineteenth century America or in the many parts of today’s America skeptical of Washington D.C., science and especially, Democrats and big city dwellers.

Patrick Henry, famous for his slogan “Give me liberty or give me death,” was excoriated by the courtly Thomas Jefferson as an unlettered fool, but nonetheless a useful one. In today’s politics, Tea Partiers whose logo contains the iconic “Don’t tread on me” are reprising the age-old culture of the borderlands: better to die fighting than succumb to outsiders and their attempt to influence one’s behavior.

In this case however, I fear that retributive justice will be meted out by COVID-19 rather than by the elites so scorned and yet so feared by Trump supporters, today’s version of Fischer’s borderland individualists.

I appreciate your research in this reactionary response to the impersonal nature of a virus. It is sobering and our inbred fear of “other” is not just American, of course. But the deep roots in the U.S. are sadly enlightening.

LikeLike

Yes. I was really struck by how contemporary politics resembles not just early America, but as Fischer makes so clear, the culture of the borderlands of Britain. What’s old is new again, alas. This probably also plays into the Brexit controversy there now that I think of it!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, truly fascinating. Considering how much of the world counted themselves a part of the British empire over the years, I wonder if there are parallels to modern politics in other geographies it colonized or controlled (e.g., India).

LikeLike

Indeed!

LikeLike

This is absolutely fascinating. I’m sharing it.

LikeLike

Thank you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] Andrew Jackson, Donald Trump and the Refusal to Wear Masks — THE MEMOIR LIFE […]

LikeLike

Stopped over from Martha Kennedy’s post. This is a very interesting read… I may have to send my mother here as this is such a good post!!

LikeLike

Thank you for visiting and commenting 😊

LikeLike

Hillbilly Elegy is another window on this scot-irish culture… https://www.amazon.com/Hillbilly-Elegy-Memoir-Family-Culture/dp/0062300547. One of the better sections, is when JD Vance realizes he sees more in common for his family history in the African-American Experience in America than he does in the traditional text books…

LikeLiked by 1 person

And particularly the book shows the persistence of culture as families move.

LikeLiked by 1 person

How silly of me to think you had not already read it.

LikeLike

😉

LikeLike

You’re right, it’s too pat. But there is some element of truth in it.

LikeLike

The back country ethic is simply selfishness. The tea party slogan should be shouted into an echo chamber: don’t tread on me ME ME ME ME.

LikeLiked by 1 person

What a fantastic review and commentary. The pandemic has certainly brought out the worst at this already polarized and bizarre time in our country. How interesting that there’s a connection drawn to British regional cultures. This was so interesting and insightful to read!

LikeLike

Thank you for reading and commenting, so glad you enjoyed it!

LikeLiked by 1 person

One needn’t trace it back to an English root. Given the right conditions, that kind of culture develops on its own. I suspect that America would have its share without needing to be seeded by Scotts-Irish hillbillies. The vast rural spaces that characterized America for centuries guaranteed it.

That “distinctive ideal of natural rights” isn’t always bad. Like most things, it is a good thing in reasonable doses and a bad thing to obsess over.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fischer’s point is that a very different understanding of reciprocal rights developed in New England and the Delaware Valley, also rural, but with a different cultural perspective. The frontier thesis posited by Turner helped to create the idea that American exceptionalism was due to the vast rural spaces you refer to. Interesting to think about what was “new” and what was “received attitudes.” Thanks for reading and commenting!

LikeLiked by 1 person

It has been hard enough to predict elections based on demographic voting patterns. To interpret the variety of responses to pandemic regulations based on both the sociology and history of groups seems like a stretch to me.

It is an interesting theory, but having made lots of mistakes with overly broad theories in my own life, I just don’t see it’s validity.

LikeLike

It is of course a broad generalization, but to me food for thought, not total explanation.

LikeLike

I do not follow you. If it is not a total explanation or theory of behavior, how exactly do you think it applies to choices made by individuals in the pandemic? In other words, to what extent do you think it has predictive value?

LikeLike

I enjoyed your take on applying this cultural thesis to modern politics. I have this book but have only sampled it. Your selection makes me want to delve into it deeper. Unlike a previous comment, I do believe this theory has merit, because we have seen the persistence of racial enmity in this country. These attitudes do hold over from generation to generation. Another aspect to this backcountry culture is the concept of “honor”, which we see in other cultures around the world. Feuds and duels come from this concept.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ll be interested to see what you think after you read it. I found it rang true for my family.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very good explanation. Still quite sad though, what is happening right now. At times unthinkable.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes. How much our world has changed in just six months, let alone since 2016. Thank you for reading and commenting.

LikeLike